Recipe Programming

10 min read

After years of practice, I have become a decent home cook. I can prepare a variety of tasty and nutritious meals suitable for both weeknights and more special occasions. However, like many home cooks, I have a simple strategy: I follow recipes.

Learning to cook at home is usually synonymous with learning to follow recipes. There is nothing wrong with this. Nor is following recipes as straightforward as it sounds. “Cook for three to five minutes or until lightly browned.” Five minutes have passed and no signs of color. Should I continue? Even the best recipes frequently improve through repetition, as you perform small experiments with timing, quantity, and other minor deviations from the instructions. I have gotten better at these things over time, through practice. And, sometimes, serendipity. My wife improved one recipe simply by misreading teaspoons as tablespoons.

Still, nobody would or should hire me to run a restaurant kitchen. Without a recipe, I am not confident that I can produce something delicious, even if it will probably be safely overcooked. I definitely cannot develop my own recipes, since I have only the scantest of observational understanding of how time and heat transform ingredients into a meal. I am a home cook. I am not a chef.

Like recipe cooking, recipe programming comprises working off a set of instructions to produce a working program. Like recipe cooking, recipe programming is a tremendously valuable skill—even more so than recipe cooking, as I will explain.

But just as recipe cooks are not chefs, recipe programming does not necessarily require or develop basic programming abilities. And there is a problematic tendency to conflate these two different skills. Nobody who attended a weekend home cooking workshop would declare “I am a chef!” But often students that complete a recipe programming course will declare “I know how to program!”

This misunderstanding is frequently supported by teachers and administrators who don’t understand programming themselves, and are impatient with the slow process of building up competency at something that is, in fact, hard. Somebody who attends a weekend cooking workshop will probably walk away able to cook a few simple meals. Somebody who attends culinary school may spend an entire year mastering a basic understanding of ingredients, preparation techniques, and food science. The first is a fast path to shallow but useful knowledge. The second is the necessarily slower route towards deep understanding. Both have value, but need to be differentiated.

Confusion here is also exacerbated by missing vocabulary. We cannot differentiate what we cannot distinguish. When discussing food we have good options to indicate somebody’s goals and depth of knowledge: home cook versus cook versus chef. The term recipe programming is my attempt to help. But I am unsure of the right way to refer to programming abilities grounded in the basics, rather than recipe-following. The term real programming seems to establish too much of a negative connotation. Recipe programming is in fact incredibly useful, and should be taught everywhere.

For the sake of clarity I will use the term scratch programming in contrast to recipe programming, to reflect the goal of being able to teach students to write and understand entire programs from scratch without requiring a recipe or template. I am not entirely happy with this term, but it will do for now.

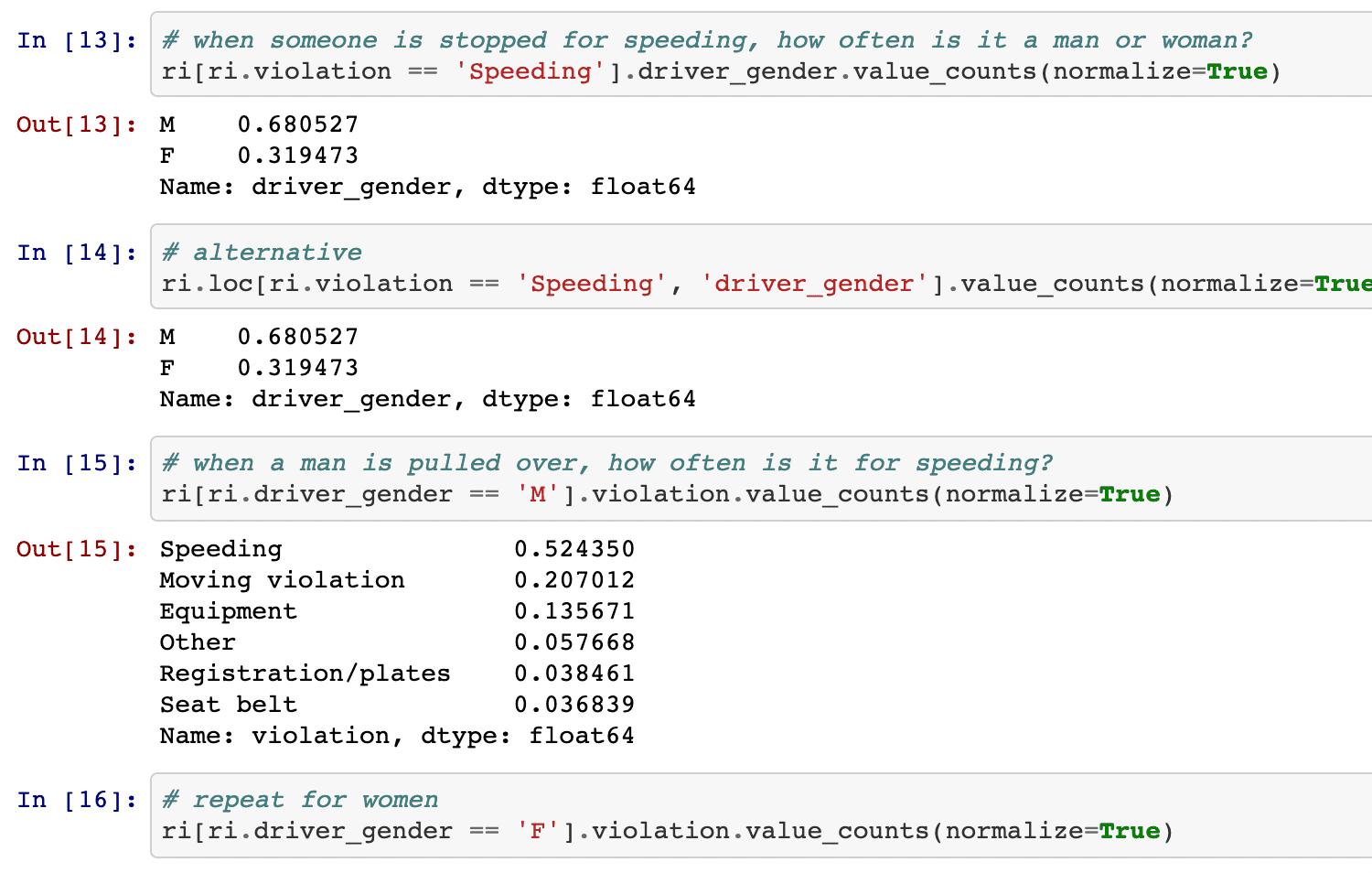

The language, environment, and task most strongly associated with recipe programming is Python in a Jupyter Notebook to perform data analysis and visualization.

If you examine code written to perform these tasks, like what is shown above, you will quickly note the characteristics of recipe programs. Recipe programs are very flat, often having no control structures, subroutines, or loops. They usually define no custom data types. Most if not all of the code consists of calls to library methods used to import, manipulate, and display data, as well as output results at intermediate stages.

Because data processing recipes can be reused on different data sets, recipe programming is extremely powerful, even more so than recipe cooking.(1) A recipe programmer can reproduce almost the exact set of steps as the recipe But, by processing different data, can reach a completely new set of conclusions. The promotional materials for fastai—a good example of an excellent recipe programming course—are full of examples of this happening.

The power of recipe programming is a great sign of how far computer science has come as a field and how much impact we are having. It is absolutely worth teaching.

But note again that recipe programs incorporate almost none of the basic programming constructs and computational thinking that we labor to explain to aspiring scratch programmers. Naturally, recipe programmers tend not to learn these things in courses on recipe programming. This itself is not a problem. It only becomes one once we think that they have.

Consider a typical first course that teaches the basics of scratch programming: variables, types, conditional and looping constructs, implementing methods, declaring custom data types, basic structures for linear and relational data, as well as computational thinking and problem solving. The specifics may and do vary, but the goal is to begin the process of producing students that can create entire programs from scratch.

What can an average student in a course like this do at the end of the semester?(2) In my course they can build a simple Android App, but usually that itself requires a fair amount of recipe-like tutorial following as well as basic Java or Kotlin abilities. In other courses the artifacts may be more or less impressive. By jettisoning a lot of the basics in favor of introducing the entire web stack, CS50 students seem to be able to produce simple web applications.

But usually we’d expect the average student that completes CS1 to be able to complete a small and fairly unimpressive program. You can make this seem more impressive in a variety of ways—including having students work on Android. And most CS1 courses, including mine, tend to promote the more impressive student projects, which are probably more the result of prior experience rather than understanding gleaned during the semester.

Now consider a recipe programming course where students focus not on understanding the basics but just on figuring out which set of library methods they need to call in what order to create a particular graph or compute a particular statistic. I think it’s fair to assume that, at the end of the semester, work produced by the students in the recipe programming course will be far more impressive than work by students in the scratch programming course. The scratch programming course is the necessarily slower route towards true understanding, while the recipe programming course is a fast path to shallow but useful knowledge.

But now consider what happens when instructors or administrators that don’t understand the distinction assess the results. Wow! Teaching data science in Python must be the magic strategy that accelerates the process of learning how to program! We should teach everything in Python. And let’s figure out how to fast-track the students from the recipe programming course into the rest of the computer science curriculum. They can probably also skip several more of the scratch programming courses as well.

Needless to say, students that have learned recipe programming are just about as prepared to continue with advanced scratch programming and computer science coursework as I am to start the second year of culinary school. Sometimes you can perpetuate this misunderstanding further by creating an additional set of parallel courses for the recipe programmers—recipe data structures! But the wheels are bound to come off at some point.

It’s worth pointing out a few other things that worsen this misunderstanding. First, data processing in Python is a sweet spot for recipe programming. I do no scratch programming in Python, but do break it out when I need to process me some data, and follow recipes just like everyone else. It works well, and this is a real and obvious strength of the Python ecosystem.

Second, there are a lot of recipe programmers in academia, and so this specific use case is even more impressive and important to them. Even a fairly sophisticated custom Android app will usually fail to interest them. But produce a stacked bar graph using MatplotLib and Pandas and their eyes light up. Familiarity breeds appreciation. This also makes them even more likely to just not really care whether students are learning the fundamentals of programming and computer science or not. The more we frontload the recipe programming skills that are useful to them, the more likely that a student will produce a graph that they can use in a publication. And that’s what matters.

The solution here is not complicated. Recipe programming and scratch programming are both extremely useful skills. As long as we are clear about what we are teaching and what students are learning, we can and should offer separate courses that teach both skills, as well as courses that blend instruction in both.

Scratch programming on its own can be quite frustrating, and it can be helpful to incorporate some recipe programming into these courses to help students have fun and build cool stuff while they are learning the basics. Learning how to follow recipes is also extremely important for scratch programmers as they perform tasks like installing software, setting up development environments, or getting started on assignments, which frequently involve needing to carefully follow a set of instructions—a recipe.

But let’s also dispense with some of the fictions supported by the confusion between recipe and scratch programming. Python is not a magically-effective language for teaching CS1. It can be used to teach scratch programming, although it’s neither the best or worst choice for that task. But a lot of its reputation probably rests on its use in recipe programming classes and misunderstandings about what students are actually learning in these courses.

Data science is also not the magically-effective topic for teaching CS1. It just happens to be a domain where recipe programming is particularly powerful and impressive. And while it is a tremendously useful skill, it’s just one of many different ways in which students can have impact through coding.

We also need to acknowledge that data science tends to be overemphasized within the academy, and make sure that our introductory courses don’t mirror that skew. We should be teaching students to build beautiful user-facing applications, the dark arts of architecting backend systems, how to program robots and embedded devices, and everything in between. Not just how to generate scatterplots.